How Can a Woman Missing Her Olfactory Bulbs Still Smell?

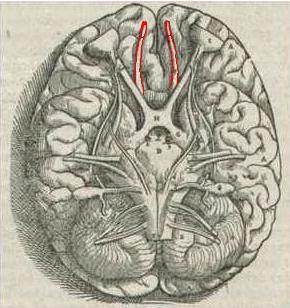

The brain’s plasticity intrigues and puzzles researcher, and it also raises a larger issueEven since neuroscientists started imaging the brain, they’ve been turning up cases where people are missing brain parts we would expect them to need in order to do something — but they are doing that very thing anyway. One example, written up in LiveScience in 2019, concerns women who are missing their olfactory bulbs (illustrated) but can still smell:

Researchers have discovered a small group of people that seem to defy medical science: They can smell despite lacking “olfactory bulbs,” the region in the front of the brain that processes information about smells from the nose. It’s not clear how they are able to do this, but the findings suggest that the human brain may have a greater ability to adapt than previously thought. – Yasemin Saplakoglu, “Women Missing Brain’s Olfactory Bulbs Can Still Smell, Puzzling Scientists,” LiveScience, November 6, 2019. The paper in Neuron is open access.

The story is all the more remarkable when we consider that her sense of smell was especially good; that was why she had signed up for the Israeli researchers’ study. Deciding to pursue the matter, the researchers tested other women. On the ninth try, they found another left-handed woman who could smell without an olfactory bulb.

A researcher who was not involved in the study, Joel Mainland of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, was asked for comment:

The findings are “pretty counter to most of what the field thinks,” Mainland told Live Science. “I think it’s pretty critical that we figure out what’s happening.”

Yes. But that could take a while because there are a number of similar situations out there.

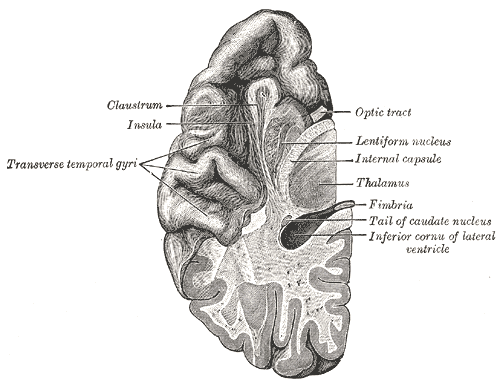

Last year, Medical Express reported on a woman who lacked a left temporal lobe (illustrated), believed to be the language area of the brain:

EG told Fedorenko and her team that she only came to realize she had an unusual brain by accident—her brain was scanned in 1987 for an unrelated reason. Prior to the scan she had no idea she was different. By all accounts she behaved normally and had even earned an advanced degree. She also excelled in languages—she speaks fluent Russian—which is all the more surprising considering the left temporal lobe is the part of the brain most often associated with language processing.

Eager to learn more about the woman and her brain, the researchers accepted her into a study that involved capturing images of her brain using an fMRI machine while she was engaged in various activities, such as language processing and math. In so doing, they found no evidence of language processing happening in the left part of her brain; it was all happening in the right. They found that it was likely the woman had lost her left temporal lobe as a child, probably due to a stroke. The area where it had been had become filled with cerebrospinal fluid. To compensate, her brain had developed a language network in the right side of her brain that allowed her to communicate normally. The researchers also learned that EG had a sister who was missing her right temporal lobe, and who also had no symptoms of brain dysfunction—an indication, the researchers suggest, that there is a genetic component to the stroke and recovery process in the two women. – Bob Yirka, “Woman with no left temporal lobe developed a language network in the right side of her brain,” Medical XPress, April 14, 2022 The paper is open access.

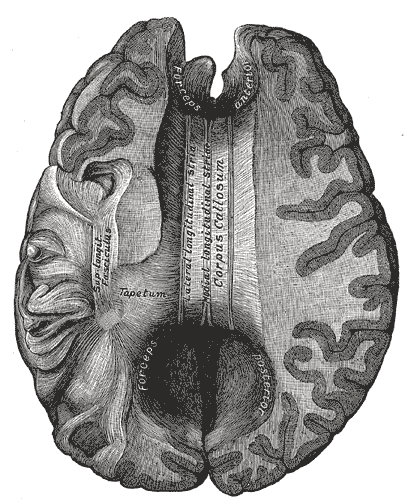

It’s also come out that one in 4000 people lacks a corpus callosum (illustrated). That’s the structure of neural fibers that transfers information between the brain’s two hemispheres. It would seem a pretty important part pf the brain yet 25% of those who lack it show no symptoms. The others suffer mild to severe cognitive disorders. But we may well wonder how people manage in this situation at all:

In a study published in the journal Cerebral Cortex, neuroscientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) discovered that when the neuronal fibres that act as a bridge between the hemispheres are missing, the brain reorganises itself and creates an impressive number of connections inside each hemisphere. These create more intra-hemispheric connections than in a healthy brain, indicating that plasticity mechanisms are involved. It is thought that these mechanisms enable the brain to compensate for the losses by recreating connections to other brain regions using alternative neural pathways. – Université De Genève, “A malformation illustrates the incredible plasticity of the brain,” ScienceDaily, October 30, 2020. The paper is open access.

Recall that, prior to brain imaging, so long as a person was functioning normally, no one had any reason to suppose that a key brain part might simply be missing. And, let’s say its absence was discovered at autopsy. Who is to say that the absence of that part didn’t play some role in bringing about the person’s death? So it was only in recent decades that researchers discovered people of normal abilities with absent brain parts. That’s probably why we hear expressions like “seem to defy medical science” and “incredible plasticity” from the science media now.

Neuroplasticity is perhaps best understood as the human mind reaching out past physical gaps and barriers in any number of inventive ways. And it raises a question: If the mind is merely what the brain does, as many materialist pundits claim, what is the mind when the brain … doesn’t? At times, the mind appears to be picking up where the brain left off.

Michael Egnor and I are looking forward to tackling topics like that in The Human Soul (Worthy, 2025).