Can Life Forms Like Spiders, That Lack a Neocortex, Really Dream?

Paleontologist Günter Bechly argues that it’s highly unlikely. Michael Egnor sides with Aristotle; they dream about what they can perceive

Recently, paleontologist Günter Bechly took issue with neurosurgeon Michael Egnor on the question of whether spiders dream. Egnor was willing to accept the possibility, noting that spiders can dream only about things they can think about: “If spiders and bacteria dream, they dream of flies or chemical gradients, but not of philosophy.” Bechly, on the other hand, thinks it’s a filament too far for the spider (never mind the bacteria) to dream at all:

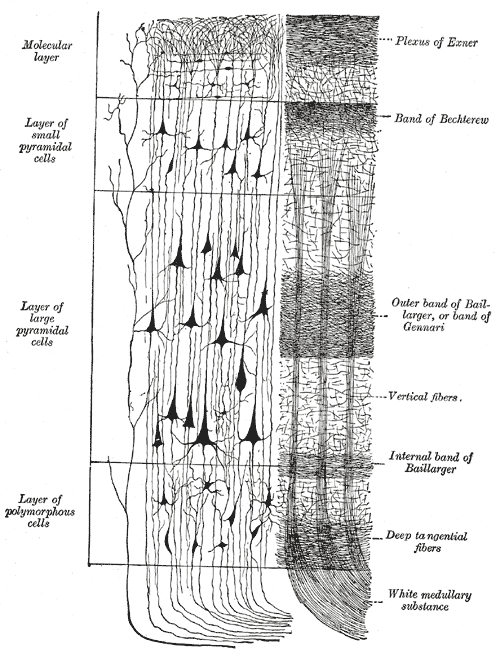

… I tend to concur with those neuroscientists who doubt any organisms possess phenomenal consciousness that lack a neocortex (found only in mammals) or a comparable structure (in birds and maybe cephalopods). Rapid eye movement may indicate neural activity, but the concept of dreaming for me implies a conscious awareness of the dream state, which I consider as highly unlikely in spiders. Spiders definitely are capable of remarkably sophisticated and seemingly intelligent behavior in their web building activity, but that behavior seems to be preprogrammed and not an achievement of their individual intelligence. But this is of course just my educated guess or gut feeling about the subject. I am open to the possibility of consciousness in lower animals but not convinced on the basis of the current evidence.

Günter Bechly, “Dreaming Spiders? My Disagreement with Michael Egnor” at Evolution News & Science Today (August 12, 2022)

The ability to wonder what being a spider is like is a gulf fixed between spiders and ourselves; they certainly aren’t imagining what it is like to be human. That said, a fair amount of research has been done recently on dreaming animals.

One philosopher, David M. Peña-Guzmán, has written a book on the topic, When Animals Dream (Princeton, 2022). He tells us that neuroscience can shed light on the question:

Fascinatingly, both PGO waves and theta oscillations have been detected in a wide variety of nonhumans. PGO waves have been discovered in animals as evolutionarily close to us as nonhuman primates and as evolutionarily distant from us as zebrafish. Meanwhile, theta oscillations, especially in the hippocampus, have been well documented in a plethora of mammals.

‘The theta rhythm disappears in slow wave sleep but reappears in REM sleep,’ explains the dream neuroscientist Antti Revonsuo. At the same time, ‘the hippocampal theta rhythm is associated with behaviours requiring responses to changing environmental information most crucial to survival: for example, predatory behaviour in the cat, and prey behaviour in the rabbit.’ The suggestion is that ‘information important for survival is accessed during REM sleep and integrated with past experience to provide a strategy for future behaviour’.

David M Peña-Guzmán, “The dreams of animals” at Aeon (June 7, 2022)

Well, Egnor would likely agree with Revonsuo. Cats dream of catching mice and rabbits dream of escaping dogs.

But then Peña-Guzmán goes on to tell us at The Scientist, “Research shows that humans aren’t the only animals whose imaginations run wild while they sleep.”

Wait a minute. Animal imaginations don’t run wild at all. Their world is the same, waking or sleeping. We know this for sure because otherwise, animals would be capable of mental feats while asleep that they cannot manage while awake.

From a review of When Animals Dream at The Atlantic, we get some sense of why it’s wise of Günter Bechly to discourage overinterpretation of animal dreams. Reviewer Camille Bromley writes,

One of the strengths of Peña-Guzmán’s book is its evocative forays into literary terrain. Our dreams, after all, are like stories. In modern philosophy, meaning-making has been tethered closely to language, which is seen as a unique ability of Homo sapiens—but in dreams, meaning arrives outside of linguistic representation. If it seems odd to consider that a mole, a raven, or even a butterfly could dream, perhaps this resistance is due to a long-standing association between dreams and imagination, creativity, and storytelling—qualities that humans typically assume are what differentiate our species from all other animals. Our dreams, as Freud suggested, are richly symbolic. They are built from memory and desire, and laden with emotion. Neurologically, to remember that something happened to you and to project scenarios in the future are very similar cognitive functions. If animals can dream, Peña-Guzmán writes, then perhaps they can also daydream, or imagine.

Camille Bromley, “Do Animals Dream?” at The Atlantic (July 18, 2022)

If we have reached the point of thinking that, because various life forms show neurological patterns that are associated with dreams in humans, then “perhaps they can also daydream, or imagine,” we need to stop and think. The demand for anthropomorphism (the assumption that animals think like humans) always greatly exceeds the supply — and today, proponents of elite Virtue causes like environmentalism and animal rights are only too happy to espouse it, whether well-grounded in neuroscience or not.

We can’t really know whether spiders dream but we can be pretty sure that their dreams would not differ from their lives.

Note: Here’s a podcast with Peña-Guzmán.

You may also wish to read: Spiders are smart. Be glad they are small. Recent research has shed light on the intriguing strategies that spiders use to deceive other spiders — and prey in general.

and

In what ways are spiders intelligent? The ability to perform simple cognitive functions does not appear to depend on the vertebrate brain as such.