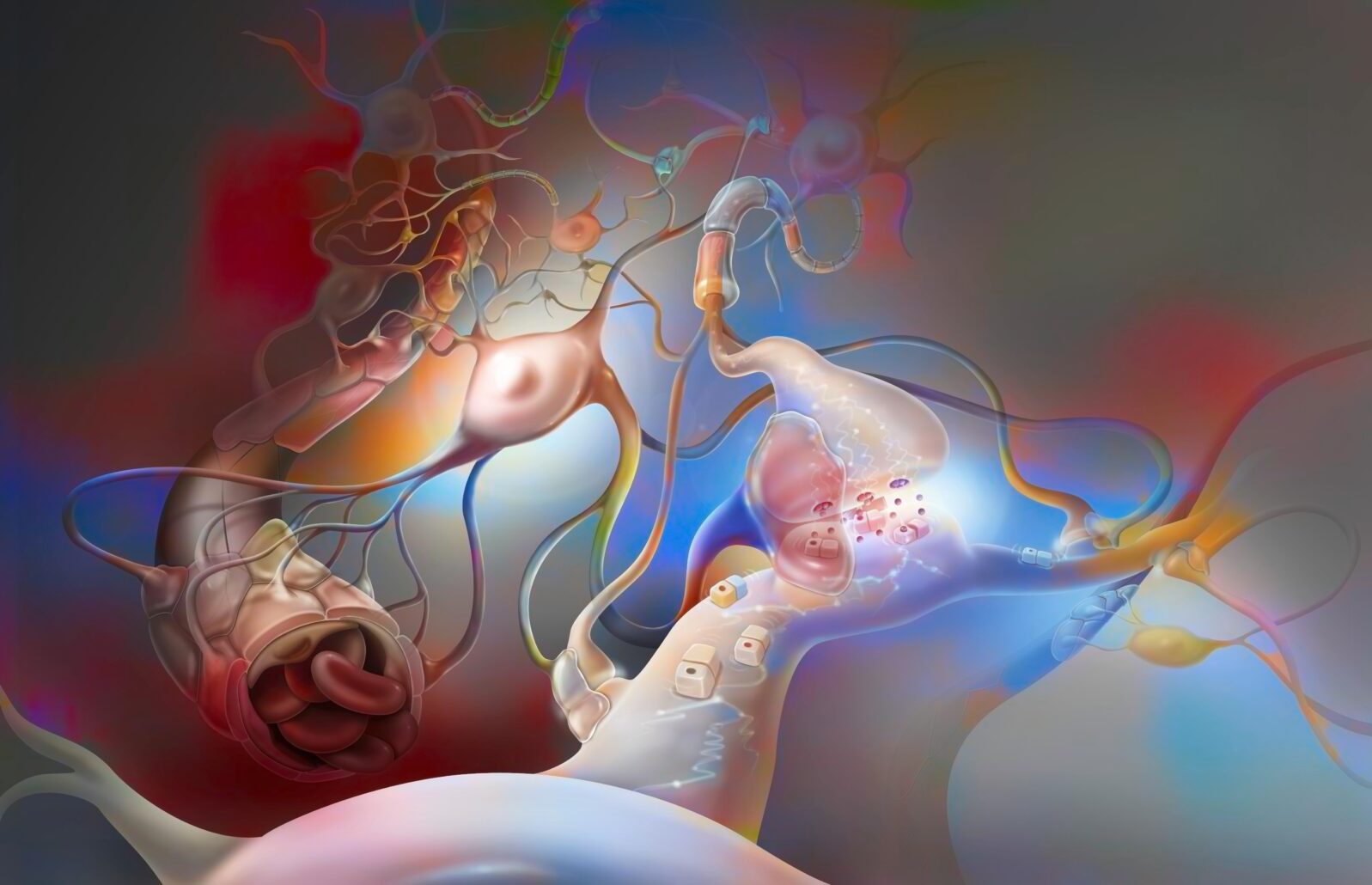

New Findings About Our Mysterious “Second Brain”

It wasn’t long ago that researchers were hardly aware of the way the digestive system functions as a second brain. The big focus was neurons. But, along with neurons, both the central nervous system and the digestive system make extensive use of glial cells, whose function has not been as well understood.

Glial cells, which do not produce electrical impulses, were considered “electrophysiologically boring.” We now know that they support neurons in both physical and chemical ways. In the gut, they co-ordinate immune responses From the Francis Crick Institute, we learn:

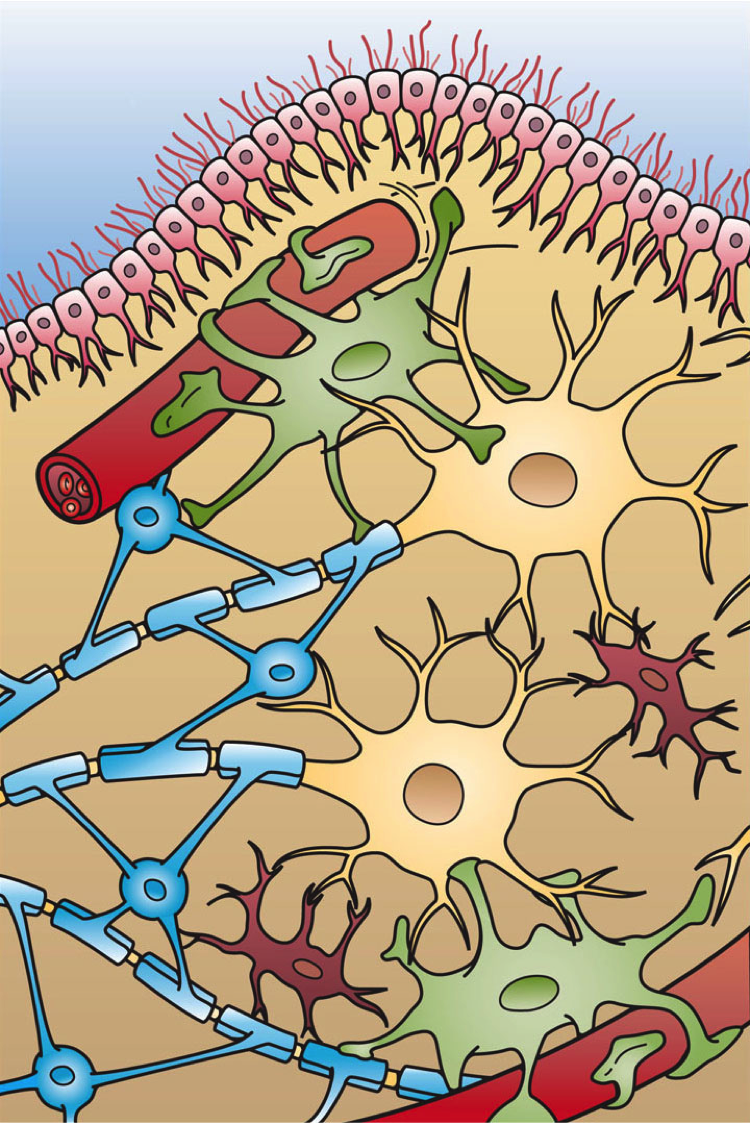

Four different types of

glial cells found in the

central nervous system,

CC by 3.0

… the enteric nervous system is remarkably independent: Intestines could carry out many of their regular duties even if they somehow became disconnected from the central nervous system. And the number of specialized nervous system cells, namely neurons and glia, that live in a person’s gut is roughly equivalent to the number found in a cat’s brain.

Mohammad M. Ahmadzai, Luisa Seguella, Brian D. Gulbransen. Circuit-specific enteric glia regulate intestinal motor neurocircuits. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2021; 118 (40): e2025938118 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2025938118 The paper is open access.

Researcher Brian D. Gulbransen explains, “In computing language, the glia would be the logic gates. Or, for a more musical metaphor, the glia aren’t carrying the notes played on an electric guitar, they’re the pedals and amplifiers modulating the tone and volume of those notes.”

Understanding how much the digestive system functions, in part, as its own brain may help researchers develop better treatment for the gut disorders that afflict about 60 to 70 million people in the United States alone.

The role microbes play

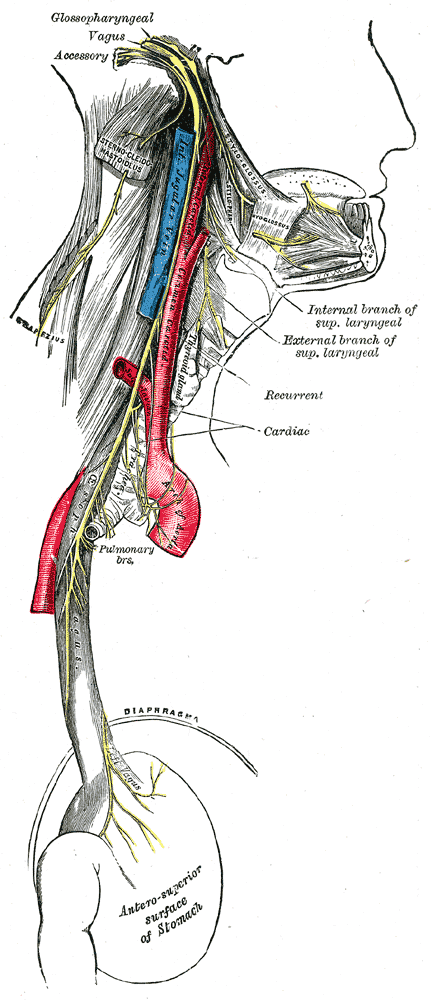

The vagus nerve is a stout cable of neurons that serves as an information highway between the base of the brain and the gut. Even though it is the longest nervous system connection in the body, messages take only milliseconds to travel between the brain and the gut.

Henry Vandyke Carter and one more author

– Henry Gray (1918)

Anatomy of

the Human Body,

public domain.

The really surprising thing is that the trillions of microbes that inhabit a human digestive system play a role in all these communications, as Heather Gerrie notes at the University of British Columbia’s neuroscience program:

Many of these microbes live in the mucus layer that lines the intestines, placing them in direct contact with nerve and immune cells, which are the major information gathering systems of our bodies. This location also primes microbes to listen in as the brain signals stress, anxiety or even happiness along the vagus nerve.

But the microbes in our gut microbiome don’t just listen. These cells produce modulating signals that send information back up to the brain. In fact, 90% of the neurons in the vagus nerve are actually carrying information from the gut to the brain, not the other way around. This means the signals generated in the gut can massively influence the brain.

Heather Gerrie, “Our second brain: More than a gut feeling,” University of British Columbia Graduate Program in Neuroscience, n.d.

Another of the remarkable qualities of glial cells is that they can shift from one type to another, as needed, in the constant battle to keep pathogens and toxins at bay.

As Yasemin Saplakoglu points out at Wired,

… scientists now know that enteric glia are among the first responders to injury or inflammation in gut tissue. They help maintain the gut’s barrier to keep toxins out. They mediate the contractions of the gut that allow food to flow through the digestive tract. Glia regulate stem cells in the gut’s outer layer, and are critical for tissue regeneration. They chat with the microbiome, neurons, and immune-system cells, managing and coordinating their functions.

Yasemin Saplakoglu, “Unpicking the Mystery of the Body’s ‘Second Brain,’” Wired, January 14, 2024

This “chat” among neurons, glia, and microbes could be important for research into the digestive system in relation to mood disorders and anxiety and depression. People often assume that their stomachs are upset because they are emotionally upset. But the story of the millions of communications shunted back and forth in milliseconds could be more complicated than that…

As Jay Pasricha, M.D., director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Neurogastroenterology, says, “The enteric nervous system doesn’t seem capable of thought as we know it, but it communicates back and forth with our big brain—with profound results.”