Will Neuroscience Ever Accommodate Immaterial Consciousness?

Joseph Green offers an informative account in Minding the Brain of the current state of neuroscience. What we now know is remarkable — but so is what we don’t“On the Limitations of Cutting-Edge Neuroscience,” which is Chapter 15 of Minding the Brain, offers neuroscientist Joseph Green’s candid assessment of the current state of the discipline. If you would like to enjoy a discussion of neuroscience today without another massive dose of promissory materialism, bookmark this one for sure.

Green starts with a premise that may be startling to some: Neuroscientists are nowhere near figuring out how the brain works. More significantly, “ no specific philosophical theory should be preferred over another on the basis of scientific findings.” That is because “ … the current dogma that pervades neuroscience—materialist monism that can be simply stated as “we are nothing but our brains”—is established by intellectual pressure rather than solid scientific evidence.” (p. 276)

Intellectual pressure indeed. Prestigious philosopher Massimo Pigliucci spelled out in an essay in Aeon in 2019 that any suggestion that our minds are not merely our brains is antiscientific. His pronouncement does not follow from any dramatic new findings. As a matter of fact, earlier this year David Chalmers, the very same non-materialist philosopher that Pigliucci was excoriating in that passage in his essay, won the famous 25-year bet with neuroscientist Christof Koch. In that agreed-on period, Koch was was unable to find the “consciousness spot” in the brain. It is definitely intellectual pressure, not achievement, that keeps materialism strong in the neurosciences.

In reality, even a simple worm is not well understood

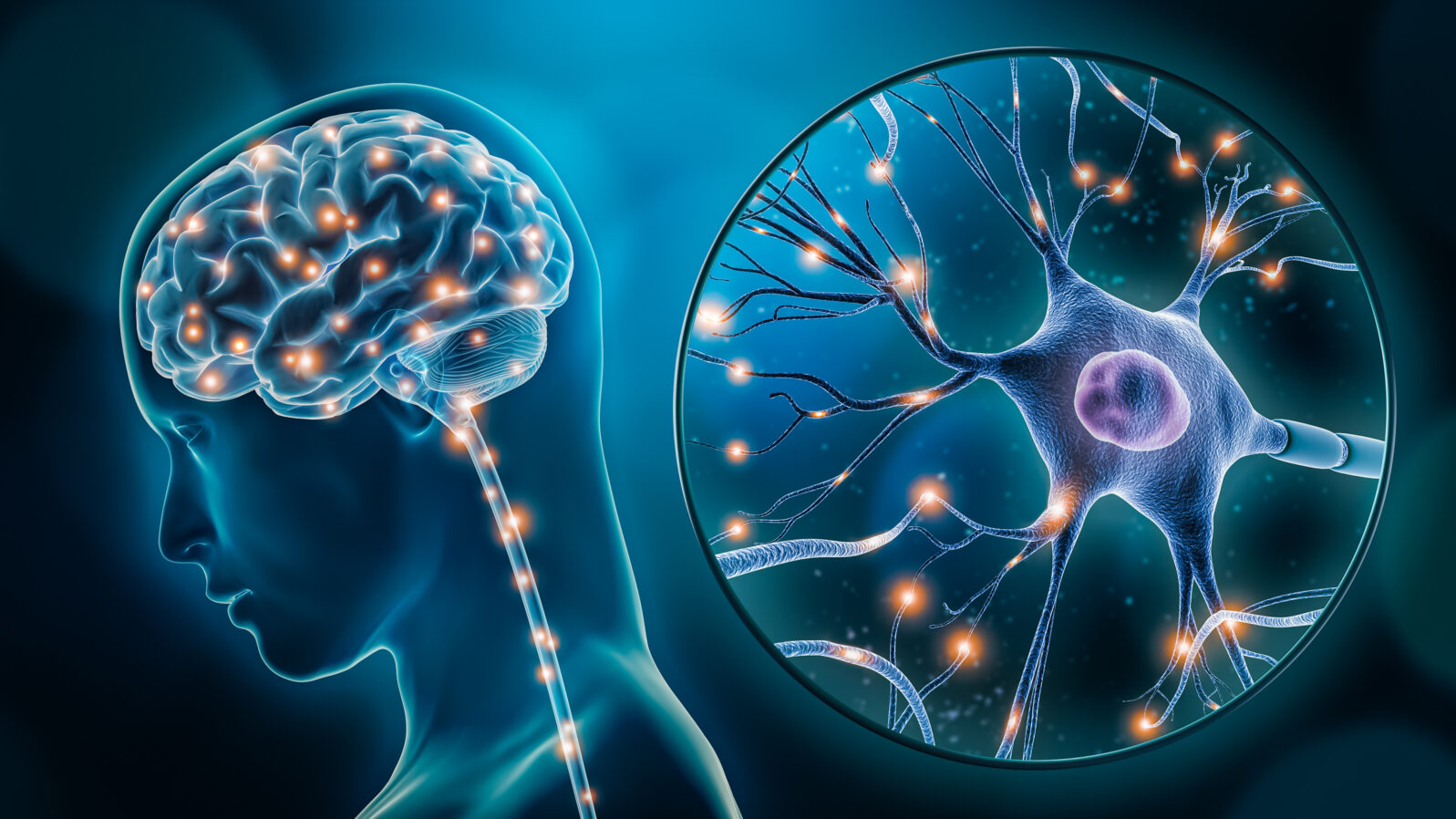

There is, Green tells us, a large knowledge gap between our ability to manipulate the brain and our understanding of how it works. That leads the public to think that neuroscience is rather more advanced than it actually is. Certainly, there have been some achievements. He cites in particular: prosthetic limbs and brain–machine interfaces that promise much better control for people living with amputations or paralysis. And also calcium recordings and optogenetics, which enable neuroscientists to study the activities of both individual neurons and large groups.

But all that information does not yield complete understanding. For example, the worm C. elegans, with only 302 neurons and pretty simple behavior patterns, is pretty much fully mapped and yet,

Despite knowing so much about such a simple neural system, it is fair to say that we yet do not understand how the animal performs the behaviors we observe. We do not understand how its decisions are generated and how neural dynamics control what it does. Of course, there have been several breakthroughs in C. elegans research, but the expectation that we would by now understand “everything” of this small system has largely gone unmet. Making sense of neural dynamics in C. elegans is an open problem to which researchers keep contributing year after year. (P, 281)

Even in more complex animals like rodents, how information is processed and integrated is not yet well understood. Does it have something to do with being a life form rather than an inanimate object?

Can neuroscience really shed light on the mind–body problem?

Green’s take must, of course, be read to be appreciated. But he argues that in the mind–body debate, neuroscientists “would be better off taking an agnostic stance rather than a monistic materialist one” because all sides can accommodate current neuroscience findings. Three areas to which he hopes neuroscience will contribute more in the future are the problem of self-consciousness, the problem of intentionality, and the binding problem.

Realistically, it’s hard to see how neuroscience could do that in its present form. Both the “self” and “consciousness” are terms for non-material entities. There aren’t metres of consciousness or kilograms of self. The problems of intentionality and binding only exist if we assume that such entities exist, but they are precisely what much neuroscience seems intended to explain away.

In its present form, neuroscience is probably only really comfortable with eliminative materialism, the idea that consciousness is an illusion. Philosopher Edward Feser explains,

The only way to hold on to the mechanistic conception of nature while rejecting dualism is thus to deny the existence of intentionality. And that is why, as John Searle has argued, all extant forms of materialism do indeed implicitly deny its existence, and thus (I would say) amount to disguised forms of eliminative materialism. This is halfway admitted by Jerry Fodor when he writes, as he does in Psychosemantics, that “if aboutness [i.e. intentionality] is real, it must be really something else.” That is to say, intentionality per se simply cannot be real given the mechanistic conception of the material world that Fodor, like all materialists, has inherited from the early modern philosophers. Hence the most the materialist can do is try to substitute for it some physicalistically “respectable” ersatz. But this is simply eliminative materialism in “folk psychological” drag; and eliminative materialism, however you dress it up, is simply incoherent.

– Some Brief Arguments for Dualism, Part II (September 26, 2008)

“Respectable ersatz” often sums it up. How else are we to regard the recent letter signed by over a hundred neuroscientists denouncing Christof Koch — not because he lost the wager with David Chalmers — but because his leading Integrated Information Theory (IIT) of consciousness might empower panpsychism and inhibit abortion. They certainly didn’t give the impression of a discipline that is particularly anxious to follow the evidence wherever it leads.

If neuroscientists are unable to shrink the mind to the brain, with absolutely no remainder, many will likely respond by attempting to shrink the discipline’s boundaries instead. That is they will declare topics like self-consciousness and intentionality to hereafter be undiscussable and unresearchable folk ideas. But they will try everything else first.

Green remains hopeful that some sort of truce with reality is possible for them. He concludes that “While some neuroscientists will undoubtedly share their opinions regarding the philosophical significance of their discoveries, their endorsement of a physicalist viewpoint (“we are nothing but our brains”) should be interpreted as a personal statement rather than one based on scientific findings” (p. 288). We must hope he turns out to be right.

You may also wish to read: The philosopher wins: There’s no consciousness spot in the brain. After a 25-year search, dualist philosopher David Chalmers won the bet with neuroscientist Christof Koch, whose consciousness theory has panpsychist overtones. As dualist neurosurgeon Michael Egnor notes, human consciousness is immaterial by nature. Is the Koch-Chalmers bet a language game aimed at avoiding that fact?