Will Mediocrity Triumph? The Fallacy That Will Not Die

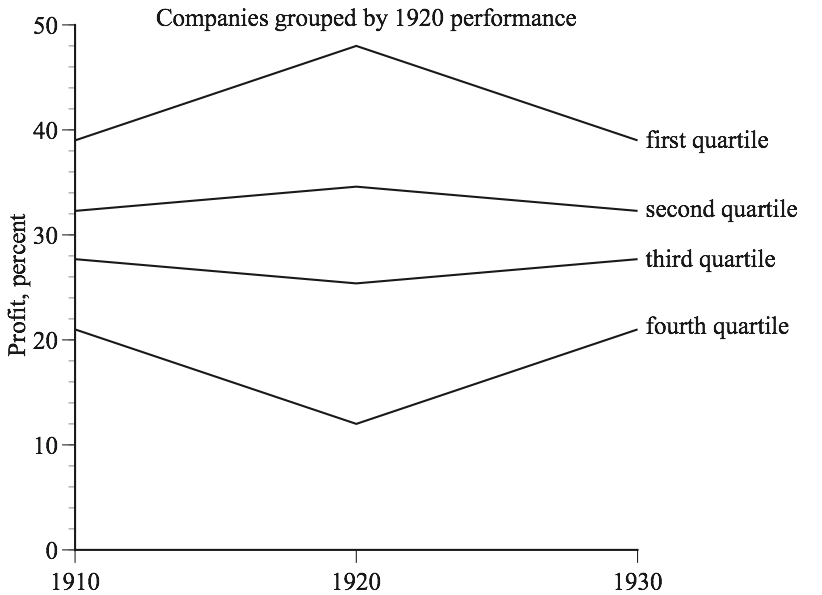

Economist claims: It is a fundamental economic truth that businesses converge to mediocrity. Is he right?Nearly 100 years ago, a famous economist named Horace Secrist wrote a book with the provocative title, The Triumph of Mediocrity in Business. He had spent ten years collecting and analyzing data on the success of dozens of companies in dozens of industries during the years 1920 to 1930. For each measure of success, he used the 1920 data to divide the companies in each industry into quartiles: the top 25%, second 25%, third 25%, and bottom 25%. He then calculated the average value of the success metric for the 1920 top-quartile companies every year from 1920 to 1930. He did the same for the other three quartiles. In every case, the companies in both the top two quartiles and the bottom two quartiles in 1920 were more nearly average in 1930.

He had evidently discovered a fundamental economic truth: businesses converge to mediocrity. Secrist’s explanation was that competitive pressures from new companies entering an industry dilute performance:

Superior judgment, merchandizing sense, and honesty, however, are always at the mercy of the unscrupulous, the unwise, the misinformed, and the injudicious. The results are that retail trade is overcrowded, shops are small and inefficient, volume of business inadequate, expenses relatively high, and profits small. So long as the field of activity is freely entered, and it is; and so long as competition is ‘free,’ and, within the limits suggested above, it is; neither superiority or inferiority will tend to persist. Rather mediocrity tends to become the rule.

The solution? Protect superior companies from competitors.

The initial reviews from eminent colleagues were unanimous in their effusive praise. The Journal of Political Economy review concluded that,

This book furnishes an excellent illustration of the way in which statistical research can be used to transform economic theory into economic law, to convert a qualitative into a quantitative science…. [T]he book reflects in a most creditable manner the painstaking, long-continued, thoughtful, and highly successful endeavor of an able statistician and economist to strengthen our knowledge of the facts and theory of competition.

The American Economic Review gushed that,

The author concludes that the interaction of competitive forces in an interdependent business structure guarantees “the triumph of mediocrity.” The approach to the problem is thoroughly scientific.

Then a brilliant statistician named Harold Hotelling wrote a devastating review that politely but firmly demonstrated that Secrist had wasted ten years proving nothing at all. What Secrist became famous for was being fooled by regression toward the mean.

This is now known as a regression fallacy. Some companies are, on average, more or less successful than others but short-run performance is also buffeted by good fortune and misfortune. The companies that happened to be the most successful in 1920 were probably not only good companies but also benefitted from some good luck. How many companies could have bad luck and still be a top performer? Their performance was not as stellar in 1930 because as a Swedish proverb says, “Luck does not give, it only lends.” Similarly, the least successful companies in 1920 were probably below-average companies that had some bad luck and could be expected to do better in 1930 simply when their bad luck was behind them.

The figure shows a stylized example of the performance of companies that have been grouped into quartiles in 1920. The 1920 data mostly show which companies were lucky and which were unlucky that year—they regress toward the mean in 1910 and 1930 because luck is fleeting.

Notice that this regression is not all the way to the mean. The best performers in 1920 were mostly above-average companies that happened to also have had some good luck. Their performance in 1910 and 1930 is still above average, just not as far above-average as in their lucky year. Their 1920 luck-aided performance exaggerates how far they are from the mean.

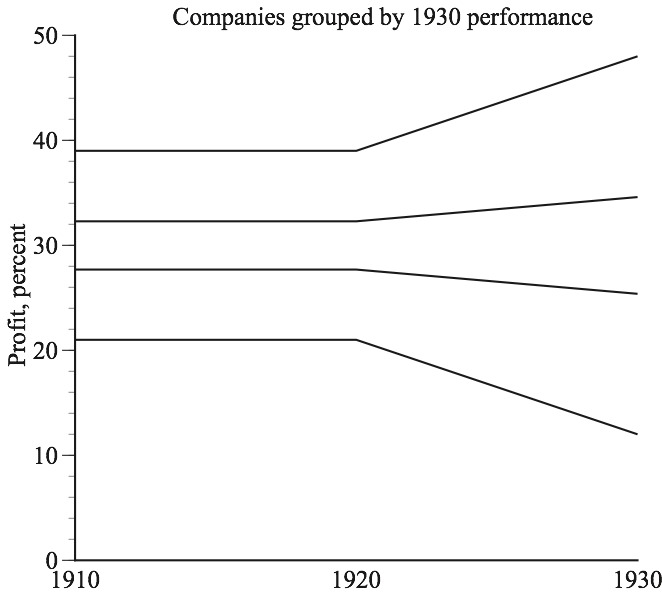

It would be a mistake to conclude, as Secrist did, that the regression toward the mean in 1930 showed that companies were converging to mediocrity. The second figure shows what happens when companies are grouped into quartiles based on the 1930 performance. There is just as much variation in performance in 1930 as there was in 1920. The only thing that changes is which companies happened to be lucky. Those with the most good luck in 1920 were, on average, not as lucky in 1910 and 1930. Those with the most good luck in 1930 were, on average, not as lucky in 1910 and 1920. The temporary nature of luck tells us nothing at all about whether competitive pressures are driving companies towards mediocrity.

Many have stepped into the same regression trap that Secrist fell into. A 1980s investments textbook written by a Nobel Prize laureate looked at the firms with the highest and lowest profit in 1966 and found that 14 years later, in 1980, the profits for both groups were closer to the mean. He concluded triumphantly, “[U]ltimately, economic forces will force the convergence of the profitability and growth rates of different firms.” Déjà vu, déjà vu. Like Secrist 50 years earlier, he did not consider the possibility that this convergence is simply regression to the mean.

Several years later, two other distinguished finance professors—including another Nobel laureate—made exactly the same error. They found earnings regression in their data and, like Secrist, attributed it entirely to competitive forces:

In a competitive environment, profitability is mean reverting within as well as across industries. Other firms eventually mimic innovative products and technologies that produce above normal profitability for a firm. And the prospect of failure or takeover gives firms with low profitability incentives to allocate assets to more productive uses.

Competitive forces may exist. But they are not the whole story. Part of the story—perhaps the whole story—is the purely statistical observation that the fickle nature of luck exaggerates the performance of the most and least successful companies.

Another variation on Secrist’s pitfall is that companies that experience a sharp downturn may bring in highly-paid management consultants to find the causes and solutions. The consultants poke around for a while, make some recommendations, and the company miraculously improves. The regression principle tells us that companies doing poorly are more likely to have been experiencing bad luck than good luck and, so, will probably do better in the future, whether or not the consultants’ recommendations have any merit or, indeed, whether consultants are even hired.

There is also regression in the results of mental and physical tests. The students who get the highest scores on one test usually do not do as well on a second test. At the other end of the spectrum, students who are given special tutoring because of their poor performance on one test generally do better on a subsequent test even if the tutor does nothing more than wave a hand over their heads. Patients with worrisome medical test results who are given special diets generally improve even if the dietary instructions are nothing more than, “Talk to your food before eating it.” Pilot cadets who have the best flights during a training session generally do not do as well on their next flight, whether the instructor praises them, screams at them, or says nothing at all.

Movie sequels are seldom as good as the originals. (If you want a sequel to be better than the original, make a sequel of a bad movie!) Parents who are unusually tall, intelligent, or athletic tend to have less exceptional children (and children who are unusually tall, intelligent, or athletic tend to have less exceptional parents).

Regression is rampant in sporting events. Athletes and teams that do extraordinarily well at the start of a season usually do not do as well the remainder of the season. Athletes and teams that win championships usually don’t repeat; for example, 60 percent of the golfers who win one of the four major golf championships never win another one. Athletes who appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated do not perform as well afterward.

Regression happens whenever we make comparisons that involve an element of luck. The most highly rated generally have had more good luck than bad and are not as far above-average as they seem. Nor are the lowest rated as far below-average as they seem. Our lives and the world around us are not slogging to a depressing mediocrity with all companies equally profitable and all people equally tall, intelligent, healthy, and athletic.

Our lives are much more interesting than that. We are constantly buffeted by temporary bursts of good luck or misfortune. Our challenge is to recognize the important role of luck in our lives and not overreact. Life is a bumpy highway, but we should enjoy the ride.